Kidney Medication Safety Checker

Kidney Medication Safety Checker

This tool helps determine your estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and identifies whether common medications like NSAIDs may be unsafe for your kidney function. Based on KDIGO guidelines and NHS Kidney Care recommendations.

Enter your information to see your kidney function and medication safety recommendations

Every year, tens of thousands of people end up in the hospital with sudden kidney failure - not from an infection, not from trauma, but from a pill they took for a headache, a backache, or even a routine dental procedure. This isn’t rare. It’s common. And worse, it’s often preventable.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Kidney Failure?

Drug-induced kidney failure, more accurately called drug-induced acute kidney injury (DI-AKI), happens when a medication damages your kidneys so badly that they suddenly stop working properly. This isn’t slow, gradual damage. It’s fast - sometimes within hours or days. Your kidneys filter waste, balance fluids, and regulate blood pressure. When a drug messes with that system, your creatinine levels spike, urine output drops, and your body starts to flood with toxins.

According to the latest guidelines from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO), DI-AKI is diagnosed if your creatinine rises by 0.3 mg/dL or more within 48 hours, or if you’re making less than 0.5 mL of urine per kilogram of body weight for six straight hours. That might sound technical, but here’s what it means in real life: you feel tired, swollen, nauseous, or confused. Your doctor sees a lab result that doesn’t match your history - and suddenly, you’re in the hospital.

It’s not just one drug. It’s a whole group. Antibiotics like vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam, painkillers like ibuprofen and naproxen, contrast dyes used in CT scans, and even common acid reducers like omeprazole can trigger this. In fact, medications are responsible for about 20% of all acute kidney injuries in hospitals - and up to 60% in intensive care units.

Three Ways Drugs Hurt Your Kidneys

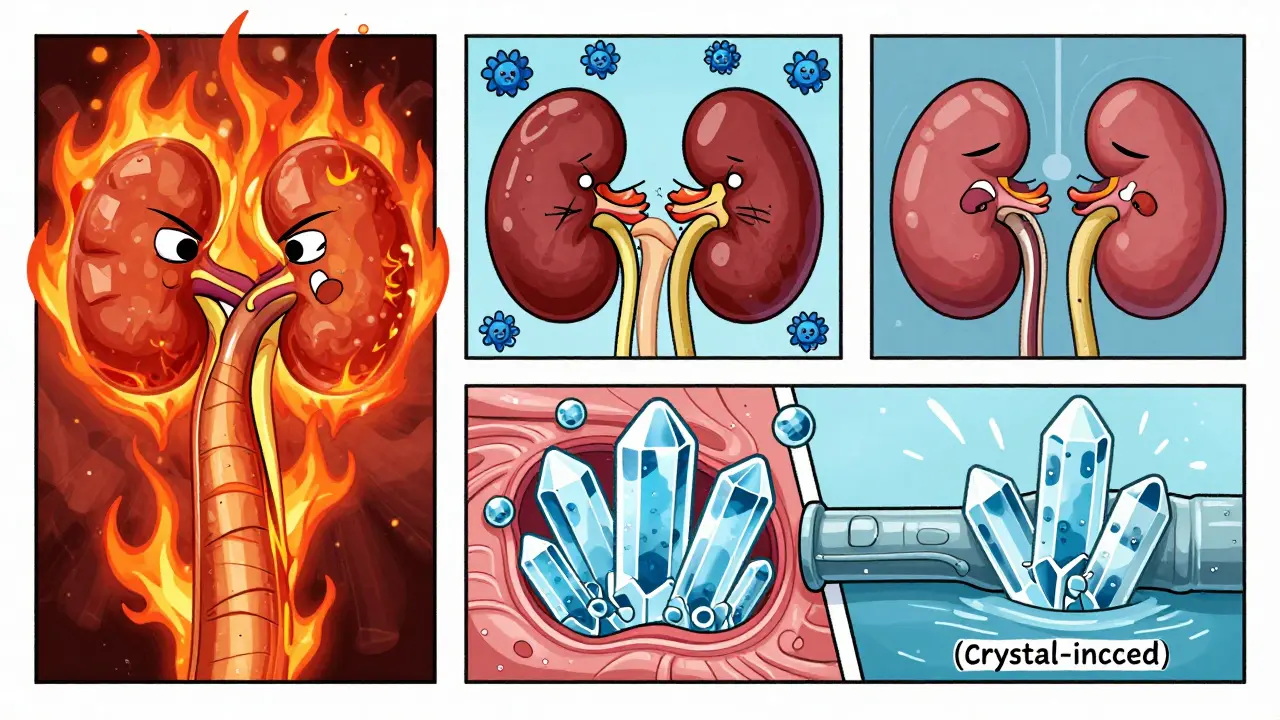

Not all drug-related kidney damage works the same way. There are three main patterns, each with different signs and treatments.

- Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN): This is an allergic-type reaction. Your immune system attacks the spaces between kidney tubules. It’s often caused by proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), penicillin, or NSAIDs. Symptoms show up 7 to 14 days after starting the drug: fever, rash, swollen glands, and blood in the urine. Eosinophils - a type of white blood cell - rise in your blood. Stop the drug, and your kidneys often bounce back. Wait too long, and scarring sets in.

- Acute tubular necrosis (ATN): This is direct poisoning of kidney cells. Drugs like aminoglycosides (gentamicin), vancomycin, and contrast dye kill off the tiny filtering units. You might not feel anything at first. But your creatinine climbs, your urine output drops, and your body can’t clear waste. This is common after major surgery or in ICU patients on multiple drugs.

- Crystal-induced nephropathy: Some drugs turn into crystals inside your kidneys. Acyclovir (for herpes), sulfadiazine (for infections), and even some HIV drugs like tenofovir can do this. The crystals clog the tubules like sand in a pipe. It’s sudden, painful, and reversible - if caught early. Drinking lots of water and making your urine less acidic (pH above 7.1) can dissolve the crystals and save your kidneys.

Who’s at Risk? It’s Not Just the Elderly

You might think only older people or those with chronic kidney disease are at risk. But that’s not true. While risk goes up with age and existing kidney problems, even healthy people can get hit.

Here’s who’s most vulnerable:

- People with eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73m² - that’s stage 2 or higher chronic kidney disease

- Those on multiple medications (five or more) - polypharmacy triples your risk

- Dehydrated patients - from vomiting, diarrhea, or just not drinking enough

- Diabetics and heart failure patients - their kidneys are already under stress

- People taking NSAIDs long-term - even over-the-counter ones

A 2023 study of over 2 million hospitalized patients found that 15-20% of those with severe AKI died. That’s one in five. And 76% of those cases were preventable.

The NSAID Trap: The Most Common Culprit

NSAIDs - ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac - are the most frequent offenders. They block chemicals your kidneys need to maintain blood flow. In a healthy person, that’s usually fine. In someone with low kidney function, it’s dangerous.

Here’s the hard truth: if your eGFR is below 60, you should avoid NSAIDs entirely. Not just reduce them. Avoid them. Studies show stopping NSAIDs in this group cuts kidney injury risk by 47%.

One patient, JohnD_72, posted on the American Kidney Fund forum: “I took ibuprofen for 10 days after dental surgery. I had CKD stage 3. My creatinine jumped from 1.8 to 4.2 in three days. My doctor didn’t connect the dots for five days. I ended up in the hospital for a week.”

That’s not an outlier. The FDA’s adverse event database shows 1.8 cases of kidney failure per 1,000 patient-years for NSAIDs. For vancomycin, it’s 2.7. For piperacillin-tazobactam, it’s 2.1. These aren’t rare side effects. They’re predictable outcomes.

How to Prevent It - The Three Rs Framework

The NHS Kidney Care team developed a simple, powerful system called the “three Rs”: Reduce risk, Recognize early, Right response. It’s not rocket science. It’s basic medicine done well.

- Reduce risk: Before prescribing any drug, ask: Is this necessary? Can we use something safer? For pain, try acetaminophen instead of ibuprofen. For acid reflux, use the lowest effective dose of a PPI for the shortest time. For imaging, ask if contrast is truly needed - and if it is, make sure you’re hydrated.

- Recognize early: Always check creatinine and eGFR before starting high-risk drugs. Don’t wait for symptoms. If you’re on a new antibiotic or painkiller, get a blood test after 3-5 days. Watch for reduced urine output, swelling in the legs, or unexplained fatigue. If your creatinine rises by 0.3 mg/dL in 48 hours, stop the drug immediately.

- Right response: Stop the offending drug. Don’t wait for confirmation. Rehydrate with IV fluids if needed. Adjust doses for kidney function. Use the Cockcroft-Gault or MDRD formula to calculate your eGFR - don’t guess. For crystal-induced injury, alkalinize urine with sodium bicarbonate and push fluids to over 3 liters per day.

One patient, MaryK_65, shared: “My cardiologist switched me from naproxen to acetaminophen after my eGFR dropped to 52. My kidney function stabilized in two weeks. No hospital stay. No dialysis. Just a smart change.”

What Hospitals Are Doing Right - and Wrong

Some hospitals are getting better. Those with computerized systems that flag risky prescriptions when a patient’s eGFR is low have reduced inappropriate dosing by 63%. Electronic alerts that say “Stop NSAID - eGFR 45” save kidneys.

But too many still fail. The NCEPOD 2019 report found that 38% of AKI cases happened because doctors kept giving nephrotoxic drugs even after knowing the patient had kidney damage. In 31% of cases, no baseline creatinine was even checked before starting the drug.

And here’s the kicker: hydration protocols for contrast dye? Only half the hospitals do them right. Sodium bicarbonate? Doesn’t work better than plain saline, according to the PREVECT trial. N-acetylcysteine? Cochrane reviewed 72 studies and found zero benefit.

What does work? Simple, consistent steps: check kidney function before, hydrate before and after contrast, avoid NSAIDs in high-risk patients, and stop the drug the moment AKI is suspected.

The Future: AI and Personalized Prevention

In 2024, the FDA approved the first AI tool designed specifically to prevent drug-induced kidney injury. Called Dosis Health, it scans patient records, checks kidney function, flags risky drug combinations, and recommends safer alternatives - all in real time. In a trial of over 15,000 patients, it cut DI-AKI cases by 41%.

Research is also moving toward genetic testing. Some people have gene variants that make them extra sensitive to certain drugs. In the next five years, we may see personalized dosing based on DNA, not just weight and age.

But you don’t need AI to protect yourself. You need to be informed.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t have to wait for your doctor to act. Here’s your checklist:

- Know your eGFR. Ask for it at your next checkup. If you don’t know it, assume it’s low if you’re over 65, diabetic, or on long-term meds.

- Never take NSAIDs daily unless your doctor says it’s safe - and even then, get your kidneys checked every 3 months.

- Before any imaging with contrast dye, ask: “Can you do this without contrast? If not, will you hydrate me before and after?”

- Keep a list of every medication you take - including OTC and supplements - and bring it to every appointment.

- If you feel worse after starting a new drug - swollen, tired, urinating less - call your doctor immediately. Don’t wait.

Drug-induced kidney failure isn’t a mystery. It’s a failure of systems - not science. We know how to stop it. We just have to do it.

Can over-the-counter painkillers really cause kidney failure?

Yes. NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen are among the most common causes of drug-induced kidney injury. They reduce blood flow to the kidneys. If you have even mild kidney impairment (eGFR under 60), diabetes, heart failure, or are dehydrated, taking these regularly can cause sudden kidney damage - sometimes within days. Acetaminophen is a safer alternative for most people.

How do I know if a drug is harming my kidneys?

You won’t always feel it. Symptoms like fatigue, swelling, or reduced urine output can be subtle. The only reliable way is a blood test measuring creatinine and calculating eGFR. If your creatinine rises by 0.3 mg/dL or more in 48 hours, or your urine output drops below 0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours, you may have acute kidney injury. Always get tested before and after starting new medications.

Is kidney damage from drugs always permanent?

Not always. If caught early and the drug is stopped immediately, many cases of drug-induced kidney injury can fully recover - especially acute interstitial nephritis and crystal-induced injury. But if the damage continues for weeks or months, scarring can occur, leading to chronic kidney disease. Early action is everything.

Should I avoid all medications if I have kidney problems?

No. Many medications are safe with proper dosing. The key is to avoid nephrotoxic ones when possible and adjust doses based on your kidney function. For example, antibiotics like amoxicillin are usually safe. But vancomycin or gentamicin need close monitoring. Always ask your doctor or pharmacist: “Is this safe for my kidneys? Does the dose need to change?”

What should I ask my doctor before starting a new drug?

Ask these three questions: 1) Is this drug known to affect the kidneys? 2) Has my kidney function been checked recently? 3) Do I need a different dose because of my kidney health? If they can’t answer, get a second opinion. Your kidneys can’t tell you when they’re in trouble - you have to be their advocate.

Preventing drug-induced kidney failure isn’t about avoiding medicine. It’s about using it wisely. The tools are simple. The knowledge exists. What’s missing is the consistent, patient-centered action - from doctors, pharmacists, and patients alike.

I’ve been on NSAIDs for years for my back pain. My doctor never mentioned kidney risk. Now I’m scared to even take Tylenol. I’m going to ask for an eGFR test next week. Thanks for the wake-up call.

big pharma is poisoning us on purpose. they dont want you healthy they want you dependent. the fda is in their pocket. your kidneys are just collateral damage in their profit game. dont trust doctors. dont trust labs. trust yourself. they dont want you to know about natural remedies. alkaline water saves lives.

why are we even talking about this like its a big deal people take ibuprofen every day and live to be 90. i had a friend take naproxen for 15 years and he still runs marathons. stop scaring people with stats. if you dont want to get kidney damage dont take drugs. duh. why is this an article

OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE BEEN TAKING IBUPROFEN EVERY DAY FOR MY PERIODS 😱 I’M GOING TO SWITCH TO ACETAMINOPHEN TOMORROW. THANK YOU FOR THIS. 🙏❤️

Excellent breakdown. The three Rs framework is clinically sound and aligns with KDIGO guidelines. One addition: always consider drug-drug interactions. For example, combining NSAIDs with ACE inhibitors or diuretics in elderly patients multiplies AKI risk by 3.5x. Also, eGFR estimation using CKD-EPI is more accurate than MDRD in most populations. Don’t rely on automated lab flags alone - manual review is essential.

people are so lazy they dont even read the label. if you take drugs without knowing the risks you deserve what you get. doctors are overworked but its still your body. check your numbers or die. simple

It’s funny how we treat kidneys like they’re indestructible. We wouldn’t pour gasoline into a car engine and expect it to run fine. Why do we treat our bodies any differently? Maybe we need to stop thinking of medicine as a quick fix and start seeing it as a long-term partnership.

I work in a rural clinic. We don’t have fancy AI tools. We have patients who drive 2 hours for a checkup. We ask: What meds are you on? Are you drinking enough water? Have you been feeling off? That’s prevention. It’s not glamorous. But it works. We saved 12 kidneys last year just by talking.

This is the kind of public health education we need more of. Not fearmongering. Not corporate propaganda. Just clear, evidence-based facts delivered with care. I’ve shared this with my book club. We’re all going to get our eGFR checked. Thank you for doing the work.

you think this is bad wait till you find out how many people die from antibiotics that are prescribed for viral infections. the system is broken. doctors prescribe because theyre pressured to do something. patients demand pills. nobody wants to wait. its a cycle of ignorance and greed.

in india we dont have access to eGFR testing in villages. people take ibuprofen like candy. they die quietly. no one records it. this is a first world problem dressed up as global health. you talk about AI but half the world cant even get clean water. stop pretending this is about knowledge. its about privilege.

my sister had kidney failure after a CT scan. they didn’t even ask if she was diabetic. i cried for weeks. now i call every doctor before they prescribe anything. i’ve become a medical ninja. if you don’t check my meds i’ll show up at the hospital with a binder. i’m not joking. 💪🩺

It makes me wonder if our entire medical paradigm is built on the assumption that the body is a machine to be fixed, rather than a living system to be nurtured. We treat symptoms with chemicals while ignoring root causes: dehydration, stress, poor diet, lack of sleep. What if the real solution isn’t a safer drug, but a different way of living? What if the kidneys are just the canary in the coal mine, screaming because we refuse to hear anything but the next prescription?

the fact that this even needs to be explained is embarrassing. people should know this. if you dont know what nephrotoxic means you shouldnt be allowed to walk into a pharmacy. this is basic biology. how are we still having this conversation in 2025

Thanks for the eGFR tip - I got mine tested yesterday. 58. I’m switching to acetaminophen and cutting out NSAIDs cold turkey. Also started drinking more water. Feels weird to be this proactive, but I’d rather be alive than ‘fine’.