When you pick up a prescription, do you ever wonder why your copay for a generic pill is $5 while the brand-name version costs $30? That’s not an accident. It’s the result of deliberate state policies designed to push doctors, pharmacists, and patients toward cheaper, equally effective generic drugs. Across the U.S., states have built a patchwork of financial and regulatory tools to make generics the default choice-and it’s working. But not always as smoothly as intended.

How States Push Doctors and Pharmacies Toward Generics

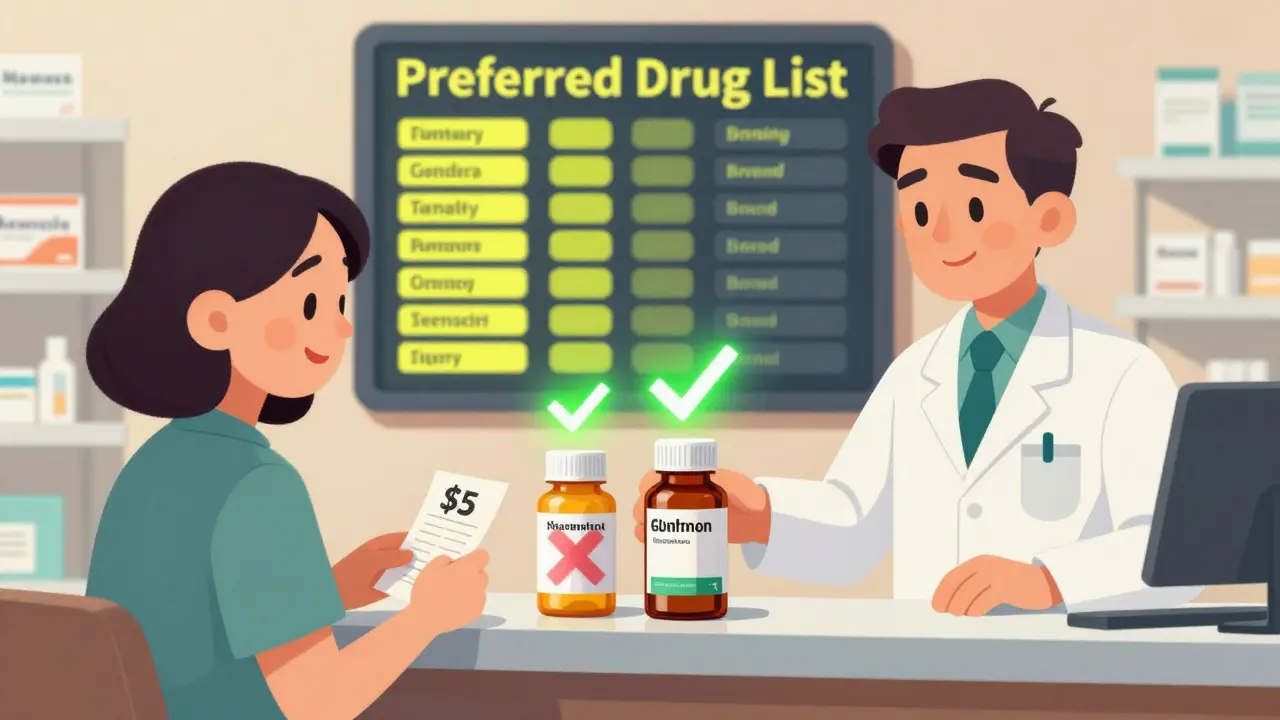

Most states don’t force doctors to prescribe generics. Instead, they make it easier and cheaper to do so. The most common tool is the Preferred Drug List (PDL). Think of it like a grocery store’s sale rack: if a drug is on the list, you get a better price. If it’s not, you pay more-or need special approval just to get it.

As of 2019, 46 out of 50 states used PDLs for their Medicaid programs. These lists are managed by Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committees, which review drugs based on cost, safety, and effectiveness. States that update their lists quarterly (10 states) or annually (20 states) can quickly remove expensive brand-name drugs and add new generics as they become available.

But here’s the twist: even if a drug is on the list, a doctor can still prescribe the brand-name version. The state doesn’t block it-they just make it harder to justify. If a doctor wants to prescribe a non-preferred drug, they often need prior authorization. That means extra paperwork, delays, and sometimes a phone call to the pharmacy benefit manager. It’s not a ban. It’s a nudge.

Why Your Copay Is Lower for Generics

One of the most effective tools states use? Copayment differentials. If your insurance plan charges $40 for a brand-name drug and $5 for the generic, you’re not just saving money-you’re being financially rewarded for choosing the cheaper option.

Studies show that when the gap between brand and generic copays is wide, patients switch. A 2000 Kaiser Family Foundation report found that even as pharmacy profits from dispensing generics and brands narrowed to just 8 cents per prescription, patient copay differences kept growing. That’s because states realized: patients respond to cost, not policy.

States like New York and California now require insurers to set generic copays at no more than $5 for 30-day supplies. Some even cap them at $1 for maintenance drugs like blood pressure or diabetes meds. The goal? Make the cheaper option so attractive that choosing the brand-name drug feels like a financial mistake.

The Silent Game-Changer: Presumed Consent for Pharmacists

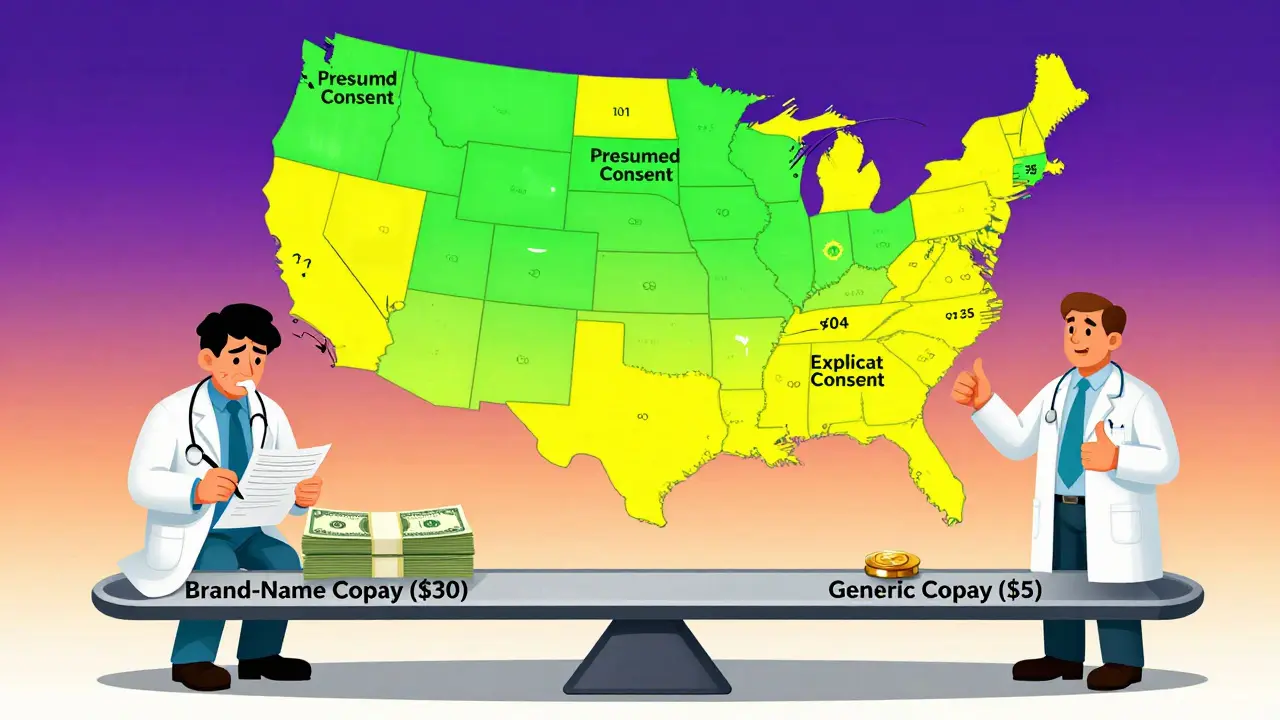

Here’s something most people don’t know: in many states, your pharmacist can swap your brand-name drug for a generic without asking you. That’s called presumed consent. In 11 states, pharmacists must get your explicit permission before substituting. In 39, they don’t have to.

A 2018 NIH study found that presumed consent laws increased generic dispensing by 3.2 percentage points-enough to save states an estimated $51 billion a year if all states adopted it. That’s more than the entire annual budget of the CDC. The reason? Pharmacists are already incentivized to dispense generics. They make slightly more profit on generics than brands. When you remove the extra step of asking permission, they just do it.

Compare that to mandatory substitution laws-where pharmacists are legally required to switch drugs. Those didn’t move the needle. Why? Because pharmacists were already substituting anyway. The law didn’t change behavior-it just added paperwork.

What Happens When Generics Disappear

It sounds simple: more generics, lower costs. But there’s a hidden problem. States rely on the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, which requires drugmakers to pay rebates to Medicaid. For generics, that’s at least 13% of the drug’s price. Sounds fair, right?

Not always. Sometimes, generic manufacturers face unexpected rebates because of market shifts-like a drug shortage, rising ingredient costs, or a sudden drop in sales volume. The Avalere Health study found five scenarios where manufacturers get hit with rebates even when prices don’t go up. In those cases, they stop selling the drug to Medicaid altogether.

That means a generic you’ve been using for years suddenly disappears from your pharmacy’s shelf. No warning. No replacement. Just… gone. And suddenly, you’re back to the expensive brand-name version-or stuck without a drug at all.

States are starting to notice. Some are now monitoring generic supply chains more closely, tracking which manufacturers are pulling out. But there’s no national system to alert them when a critical generic is at risk.

The 340B Program and the Hidden Cost of Savings

Another layer of the puzzle? The 340B Drug Pricing Program. Created in 1992, it lets hospitals and clinics that serve low-income patients buy drugs at deeply discounted prices-sometimes 20% to 50% off.

These savings are huge. A community health center in rural Ohio might save $200,000 a year on just one generic blood pressure drug. But here’s the catch: Medicaid requires states to reimburse pharmacies for 340B drugs based on the actual price they paid. So if a pharmacy buys a generic at $10 through 340B, Medicaid can’t pay them $20 for it.

CMS made this rule official in 2017. States had to adjust their reimbursement systems or risk losing federal funding. Many did. But some pharmacies now lose money on 340B generics. So they stop stocking them. Or they charge patients more. Or they stop accepting Medicaid altogether.

The irony? The program meant to lower costs is now creating unintended access barriers.

What’s Next? The Medicare Drug List

The federal government is watching. In 2023, CMS announced it was testing a $2 Drug List for Medicare Part D beneficiaries. The idea? Any generic drug that costs $2 or less per month gets a flat copay. No more complicated tiers. No more confusing formularies.

It’s not mandatory. States can’t force it. But many are watching closely. If it works for Medicare, it could become a model for Medicaid. Imagine a national list of 200 low-cost generics-all $2 or less. That could eliminate copay confusion, reduce pharmacy errors, and make generics the obvious choice for millions.

But the big question remains: can states keep the supply stable? If manufacturers keep leaving Medicaid because of rebate surprises, then even the best-designed incentive won’t matter. The system only works if the drugs are there.

What Patients Should Know

If you’re on Medicaid or a public insurance plan, ask your pharmacist: Is this the generic version on my state’s preferred list? If it’s not, ask why. Sometimes, the brand-name drug is necessary. But often, it’s just habit.

And if your generic suddenly disappears? Don’t assume it’s gone forever. Talk to your doctor. Check with other pharmacies. Call your state’s Medicaid office. These programs change fast. Your voice matters.

Why do some states require patient consent before substituting generics?

Some states require explicit consent to protect patient autonomy, especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows-like seizure or thyroid medications-where even small differences in formulation can matter. But research shows this doesn’t improve safety. In fact, it reduces generic use. States with presumed consent laws see higher generic dispensing rates without increased risks.

Do generic drugs work the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also meet the same strict standards for quality, purity, and performance. The only differences are in inactive ingredients, like fillers or dyes-which rarely affect how the drug works.

Can a pharmacist refuse to substitute a brand-name drug for a generic?

Yes-if the prescriber writes "do not substitute" on the prescription, or if the patient refuses. In presumed consent states, pharmacists can substitute without asking, but they must honor any patient or provider request to avoid substitution. They can’t override that.

Why do some generic drugs cost more than others?

Generic prices vary because multiple manufacturers may produce the same drug. If only one company makes it, they may charge more. If several companies compete, prices drop. Supply chain issues, manufacturing delays, or regulatory problems can also cause shortages and price spikes-even for generics.

Are there any states that don’t use generic prescribing incentives?

All 50 states have some form of incentive, but the strength varies. A few states, like Alaska and Vermont, have less aggressive PDLs and minimal copay differentials. Still, even those states use Medicaid rebates and 340B discounts. No state actively discourages generics-they just differ in how aggressively they promote them.

State policies on generic drugs aren’t about forcing people to choose cheaper options. They’re about making the right choice the easiest one. When copays are fair, substitutions are automatic, and supply is stable, everyone wins: patients save money, states save on healthcare spending, and pharmacies can focus on care-not paperwork.

But if manufacturers keep pulling out because of rebate surprises, or if patients can’t find their meds because of reimbursement rules, then even the smartest policy fails. The real test isn’t how many incentives states create-it’s whether the drugs are still on the shelf when you need them.