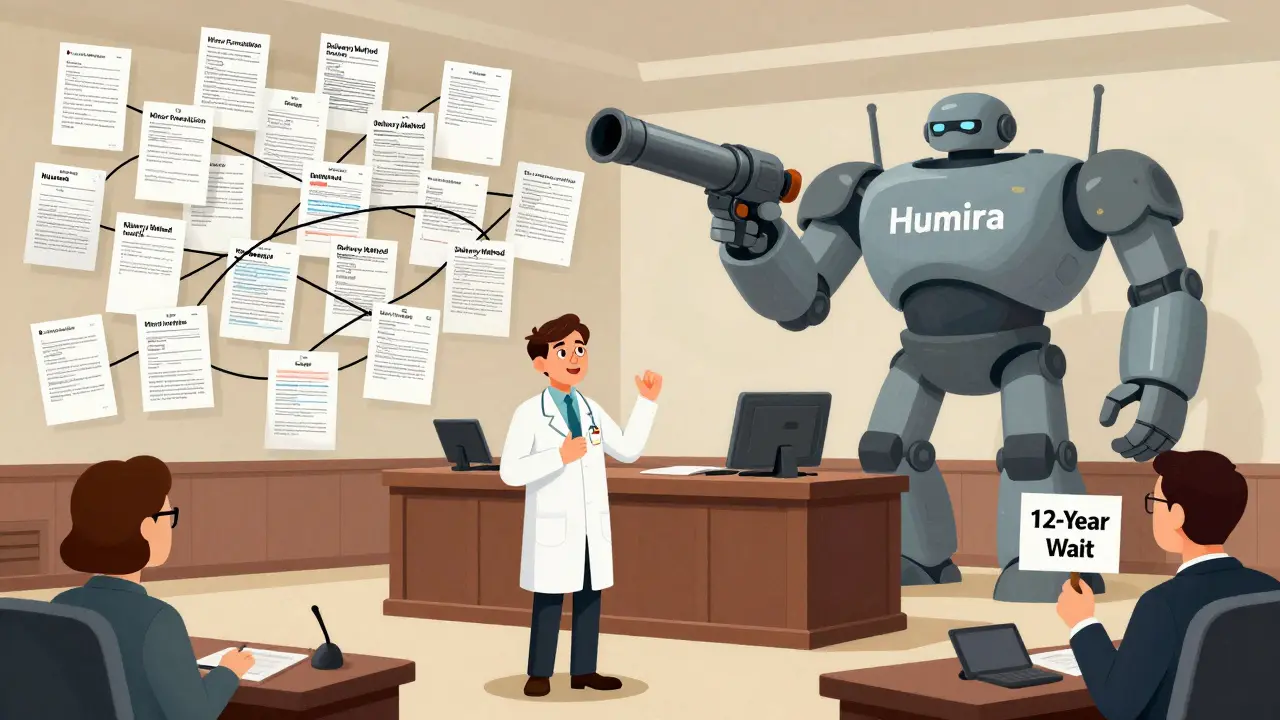

For over a decade, the U.S. has blocked biosimilars from entering the market-even after the original biologic’s core patent expired-thanks to a legal shield built into federal law. While generic versions of pills and injections can appear within months of a drug’s patent ending, biosimilars face a 12-year wait. That’s not a patent. That’s a government-mandated monopoly. And it’s costing patients billions.

What Exactly Is a Biologic?

Biologics aren’t chemicals. They’re living drugs. Made from proteins, antibodies, or cells grown in labs, they treat cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and other serious conditions. Think Humira, Enbrel, or Keytruda. Unlike small-molecule generics, which are exact copies of a chemical compound, biosimilars are highly similar versions. They’re not identical-no two living systems produce the exact same molecule-but they must show no clinically meaningful difference in safety, effectiveness, or how the body processes them. The FDA requires rigorous testing: analytical studies, animal tests, pharmacokinetic data, and sometimes clinical trials. It’s not a shortcut. It’s a science-heavy path.

The 12-Year Clock: How the Law Blocks Competition

The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) of 2009 created the rules. Under this law, once the FDA approves a new biologic, no biosimilar application can even be submitted for four years. And even after that, the FDA can’t approve any biosimilar until 12 years have passed. That’s two layers of protection: data exclusivity and market exclusivity. The first four years? No one can file. The next eight years? Applications can be filed, but they can’t be approved. Only after 12 years can a biosimilar legally hit the market.

This isn’t just about patents. Even if the original patent expires at year six or eight, the law still blocks approval until year 12. It’s a legal barrier, not a patent one. And it’s longer than most other countries. The EU gives 10 years of data protection plus one year of market exclusivity-11 total. Japan matches the U.S. at 12 years. South Korea? Just 10 years of data protection, no extra market lock. The U.S. stands out as the strictest.

The Patent Dance: Why Biosimilars Get Stuck in Court

Even after the 12-year mark, biosimilars don’t just walk in. There’s something called the “patent dance.” It’s a legal ritual required by the BPCIA. Within 20 days of submitting a biosimilar application, the maker must hand over their entire development file to the original drug company. That company then has 60 days to pick which patents they think are being infringed. The biosimilar maker responds with legal arguments. Then both sides negotiate which patents to litigate immediately.

It sounds fair. In practice? It’s a delay machine. Big pharma companies pile on hundreds of patents-sometimes dozens more than the original invention deserves. AbbVie, maker of Humira, held over 160 patents on a single drug, even though the core patent expired in 2016. That meant even after 12 years, lawsuits kept Humira off the market until 2023. The Supreme Court ruled in 2017 that companies don’t have to play along with the patent dance-but many still do, because it gives them more time to sue.

Why It Costs Patients So Much

While Europe got Humira biosimilars in 2018, the U.S. didn’t see its first until 2023. During that five-year gap, Humira’s price in the U.S. jumped 470%. In Europe? Prices dropped 40% after biosimilars arrived. That’s not coincidence. It’s market control.

Patients in the U.S. pay three times more for the same biologic than patients in Europe. For cancer drugs, the gap is even wider. One study found that U.S. patients paid 300% more for identical biologic treatments. Pharmacists report that 63% of patients have skipped or stopped biologic therapy because they couldn’t afford it. That’s not just expensive-it’s dangerous.

The Biosimilar Void: What’s Not Coming

Between 2025 and 2034, 118 biologics will lose exclusivity in the U.S. That’s a $234 billion market opportunity. But only 12 of them have biosimilars in development. Why? Three big reasons:

- Complexity: Antibody-drug conjugates, bispecific antibodies, cell therapies-these aren’t simple proteins. They’re hard to copy. Manufacturing costs can hit $250 million and take 10 years.

- Orphan drugs: 64% of expiring biologics treat rare diseases. Fewer patients means less profit. Only one orphan biologic has a biosimilar in the pipeline.

- Patent thickets: Companies keep filing new patents on minor changes-dosage, delivery method, formulation-to extend protection. It’s legal, but it’s not innovation.

There’s a growing crisis. Eighty-eight percent of expiring biologics with orphan indications have no biosimilar in sight. That means patients with rare diseases may face the same high prices for another decade.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

The big winners are the original drugmakers. They get 12 years of pricing power, often with no competition. The Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO) argues this is necessary to fund research. But critics say the system rewards legal maneuvering over real innovation. Professor Arti Rai from Duke University found that 87% of BPCIA lawsuits involve multiple patents-most of them trivial.

Patients and insurers lose. Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurers pay billions more than they should. Pharmacies report patients choosing cheaper, less effective treatments just to afford care. Advocacy groups like AARP and Doctors Without Borders call the 12-year rule an artificial barrier to affordable medicine.

And it’s not just about cost. Delayed access means more suffering. Patients with autoimmune diseases wait years for relief. Cancer patients pay more for life-saving drugs. The system isn’t broken-it was built this way.

What’s Changing?

The FDA has tried to help. Their 2022 Biosimilars Action Plan promised better communication, faster reviews, and clearer guidelines. But progress is slow. Only 38 biosimilars have been approved in the U.S. since 2015. In Europe? 88. The gap isn’t closing fast.

Legislative efforts like the Biosimilars User Fee Act of 2022 aimed to speed things up. But it stalled in Congress. Without policy changes, the biosimilar void will keep growing. Complex therapies-gene therapies, cell therapies-are next on the expiration list. None have biosimilars in development. When they expire, the U.S. could face even higher prices with no competition in sight.

What Comes Next?

The clock is ticking. By 2027, over 20 major biologics will be eligible for biosimilar entry. But without changes to the patent dance rules, without limits on patent stacking, without incentives for developers to tackle complex drugs, most of those won’t come to market for years.

The real question isn’t when biosimilars can enter. It’s whether the system will let them in at all. The law gave us 12 years. But the real cost isn’t measured in years-it’s measured in lives delayed, treatments skipped, and money wasted.

Can a biosimilar enter the U.S. market before 12 years?

No. Under the BPCIA, the FDA cannot approve any biosimilar until 12 years after the reference biologic’s first approval. Even if all patents expire earlier, the 12-year exclusivity period still applies. The only exception is if a biosimilar applicant successfully challenges a patent in court and gets a court order allowing early approval-but this is rare and legally complex.

How is a biosimilar different from a generic drug?

Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs. Biosimilars are highly similar versions of complex biologic drugs made from living cells. Because biologics are large, intricate molecules, biosimilars can’t be identical-only “highly similar” with no clinically meaningful differences in safety or effectiveness. The approval process for biosimilars is far more rigorous, requiring extensive analytical, clinical, and pharmacokinetic testing.

Why do biosimilars cost so much to develop?

Biologics are made using living cells, which makes manufacturing extremely complex. Replicating the exact structure and function requires advanced facilities, specialized expertise, and years of testing. Development can take 5-10 years and cost over $100 million-up to $250 million for complex therapies like antibody-drug conjugates. In contrast, generic small-molecule drugs cost $1-2 million and take about two years to develop.

What’s the patent dance, and why does it delay biosimilars?

The patent dance is a legal process under the BPCIA where a biosimilar applicant must share its application and manufacturing data with the original drugmaker. The original company then lists patents it believes are infringed. Both sides negotiate which patents to litigate. This process often leads to multi-year lawsuits, especially when companies file dozens of weak or overlapping patents. It’s designed to resolve disputes early-but in practice, it’s used to delay biosimilar entry for years.

Are biosimilars safe?

Yes. The FDA requires biosimilars to demonstrate no clinically meaningful differences in safety, purity, and potency compared to the original biologic. Thousands of patients in the U.S. and Europe have used biosimilars for over a decade with safety profiles matching the reference products. They are not “weaker” or “less effective.” They’re rigorously tested alternatives.

Why are so few biosimilars in development for orphan drugs?

Orphan drugs treat rare diseases with small patient populations. That means lower sales potential, making it hard for manufacturers to recoup the $100-250 million development cost. Only 1 out of 118 expiring orphan biologics currently has a biosimilar in development. Without policy incentives, companies won’t invest in these markets-even though patients desperately need affordable options.

This is pure corporate theft wrapped in legal jargon. Twelve years? That’s not innovation, that’s extortion. Patients are dying while CEOs cash in on monopoly pricing. The FDA is complicit. Congress is bought. And we’re supposed to be grateful for ‘highly similar’ drugs that still cost a fortune? No. This is a national scandal.

I’ve been on Humira for 8 years and I’ve watched the price go from $2k to $7k a month. My insurance started denying refills last year. I had to switch to a cheaper drug that doesn’t work half as well. Now I’m in more pain and my doctor says there’s nothing else to try until biosimilars arrive. Why does it take 12 years to let people get affordable medicine

So basically Big Pharma is playing monopoly with our lives 😤💸

And the worst part? They call it ‘protecting innovation’ when they’re just filing patents on the color of the pill 🤦♀️

Also why is the US the only country doing this?? 🇺🇸❌

Europe got biosimilars in 2018. We got lawsuits and price hikes. #PharmaIsARacket

The 12-year exclusivity period is a regulatory capture masterpiece. It’s not about science. It’s about rent-seeking. The BPCIA was sold as a compromise but became a corporate gift. The patent dance isn’t a process-it’s a delay tactic weaponized by legal teams with $1,000/hour billing rates. The FDA’s slow approval pace isn’t incompetence-it’s institutional inertia designed to protect incumbents. And the data shows: no correlation between exclusivity periods and R&D investment. This system enriches shareholders, not patients.

The United States must maintain its leadership in pharmaceutical innovation. Without robust intellectual property protections, the global biotech industry would collapse. Other nations benefit from American research while refusing to pay its fair share. The 12-year exclusivity period is not excessive-it is essential. To weaken it is to undermine the very foundation of medical progress. We cannot allow short-term cost concerns to jeopardize long-term scientific advancement.

There’s something deeply ironic about a society that prides itself on individual freedom yet enshrines corporate monopolies as public policy. We celebrate competition in every other market-cars, phones, groceries-but when it comes to life-saving medicine, we accept legal barriers as inevitable. Is it because we’ve been conditioned to believe health is a privilege, not a right? The 12-year rule doesn’t protect innovation. It protects profit from the consequences of its own design.

Let’s be clear-this is a biotech oligarchy. The patent thicket strategy is textbook anticompetitive behavior. Companies are gaming the system by patenting trivial variations-dosage forms, delivery devices, buffer compositions-anything to extend exclusivity. The FDA’s approval backlog is not a technical issue-it’s a political one. And the orphan drug exception? That’s not a market failure-it’s a moral failure. 88% of orphan biologics with no biosimilar? That’s systemic neglect disguised as economics. We need structural reform, not incremental tweaks.

My cousin in India got her Humira biosimilar for $100 a month. Here it’s $6k. We’re not behind on science-we’re behind on ethics. This isn’t capitalism. This is corporate feudalism.

I work in a pharmacy. I see people skip doses or split pills just to make it last. One woman told me she’d rather be in pain than bankrupt. This isn’t about drug prices. It’s about what kind of society we are.

Why should Americans pay more than everyone else for the same medicine? We fund the research so other countries get cheap drugs? That’s not fair. We need to fix this now